The other day, a friend asked a Facebook group how developments in domestic audio might shape up in the future.

Nothing, not even Dolby Atmos, beats the revelation I experienced, in the early 1980s, of

- being able to leave behind the distortion and interruptions of vinyl by using CD or tape; and

- being able to build better loudspeakers.

The story goes back fifty years, at the time of writing. In 1967, my father bolted a rescued Garrard AT6 , the autochanger based on the SP25, into a polished brown radiogram cabinet and wired the crystal cartridge to the input of the built-in valve radio/amplifier. The cabinet had a richly toned single speaker underneath, and this system of glowing radio dial and filaments played his classical LPs, the 7-inch singles my mother inherited from her DJ brother, and my children’s records, together with some shellac 78s from second-hand shops and relatives, played by turning the crystal cartridge over in its headshell.

, the autochanger based on the SP25, into a polished brown radiogram cabinet and wired the crystal cartridge to the input of the built-in valve radio/amplifier. The cabinet had a richly toned single speaker underneath, and this system of glowing radio dial and filaments played his classical LPs, the 7-inch singles my mother inherited from her DJ brother, and my children’s records, together with some shellac 78s from second-hand shops and relatives, played by turning the crystal cartridge over in its headshell.

Amid the clunks and whirs of the mechanism, I was hooked on music of all kinds,  and speech recordings too from companies like Saga and Delysé. On command, even a child could make dramatic magic happen in that warm-sounding loudspeaker. The amp with its lethal HT anode kicks was

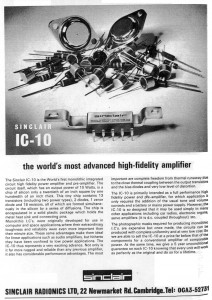

and speech recordings too from companies like Saga and Delysé. On command, even a child could make dramatic magic happen in that warm-sounding loudspeaker. The amp with its lethal HT anode kicks was  replaced in 1969 by a black box into which my father had installed a Sinclair IC10-based 10W amp, which lasted through the replacement of the cartridge with a ceramic item in 1971, then he built (with me holding the circuit-boards steady sometimes) the Practical Electronics Gemini stereo amp set in 1972. In the years of mass-market stereo LPs on “Music for Pleasure” among others, we played this amp into mis-matched speakers rescued from Army surplus shops.

replaced in 1969 by a black box into which my father had installed a Sinclair IC10-based 10W amp, which lasted through the replacement of the cartridge with a ceramic item in 1971, then he built (with me holding the circuit-boards steady sometimes) the Practical Electronics Gemini stereo amp set in 1972. In the years of mass-market stereo LPs on “Music for Pleasure” among others, we played this amp into mis-matched speakers rescued from Army surplus shops.  “But it was a stereo hi-fi to US” (to misquote Eric Idle), and the leap forward into “sound sculpted in space” was never regretted.

“But it was a stereo hi-fi to US” (to misquote Eric Idle), and the leap forward into “sound sculpted in space” was never regretted.

A Goldring magnetic cartridge followed, and a tuner, and other improvements here and there; but, as a musician-in-training, even when young, it maddened me that the music didn’t sound like it did on the radio or in the schoolroom when we played. There were ticks and pops that you didn’t get from instruments nor did you hear  them on the Radio 3 concerts. Sometimes the pitch wavered slowly. Nearly always the sound had a ‘fuzz’ with it toward the end of a side, particularly on French horns, muted brass and sopranos. None of this happened when I taped a cassette off the radio, and it was a crying shame that all recorded music for the masses had this gauze of dirt, this veil in front of it. I learned where every scratch was in the quiet passages of the symphonies and chamber music on the shelf, and was almost surprised when those noises didn’t occur where expected on radio performances. My parents didn’t mind the interruptions, but I knew this rubbish was not music, even though the frequency response ran smoothly from bottom to top and the amplifier’s distortion was almost below measurement. And it was sad that one poorly set-up pickup or arm could damage a precious recording for ever.

them on the Radio 3 concerts. Sometimes the pitch wavered slowly. Nearly always the sound had a ‘fuzz’ with it toward the end of a side, particularly on French horns, muted brass and sopranos. None of this happened when I taped a cassette off the radio, and it was a crying shame that all recorded music for the masses had this gauze of dirt, this veil in front of it. I learned where every scratch was in the quiet passages of the symphonies and chamber music on the shelf, and was almost surprised when those noises didn’t occur where expected on radio performances. My parents didn’t mind the interruptions, but I knew this rubbish was not music, even though the frequency response ran smoothly from bottom to top and the amplifier’s distortion was almost below measurement. And it was sad that one poorly set-up pickup or arm could damage a precious recording for ever.

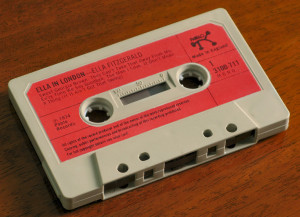

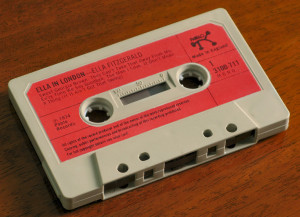

Later, in my early teens, the record-making process was unveiled to me, and it seemed strange that good tape copies of the masters were not sold to music-lovers.  “Musicassettes” too often sounded muddy, though we rescued a reel-to-reel deck to play home-recorded tapes well; but no decent tapes were available unless recorded from Radio 3 concerts or the Big Band shows on Radio 2 which were superbly presented. As you can tell, I had no idea of the economics of producing tape versus vinyl LPs.

“Musicassettes” too often sounded muddy, though we rescued a reel-to-reel deck to play home-recorded tapes well; but no decent tapes were available unless recorded from Radio 3 concerts or the Big Band shows on Radio 2 which were superbly presented. As you can tell, I had no idea of the economics of producing tape versus vinyl LPs.

But soon after that I was engineering or producing my own student recordings of good concerts or bands in our departmental studio at Surrey University; and almost simultaneously with my leaving home,  the CD came along. Teenagers (as I was then) can tell where 20kHz brickwall filters harm music, but at last, at long last, the music was almost completely pure. It did not waver or wobble. It was not interrupted by ticks and pops, nor by fuzz. Its quality was identical from beginning to end. There was no mourning that the beautiful passages of “En Saga” were harmed by being close to the end of the LP side. There was silence between the tracks or in the rests. Just like in the concert hall or recording session. And, later, it became clear that the recorded sound did not need to be sanitized (albeit, in the hands of a mastering engineer, very sympathetically and musically indeed) to survive the transition from tape to vinyl groove. After this, all else was candlelight. We didn’t have gas in the village where I grew up. (Note to the youngest readers: find Karajan’s statement on digital audio.)

the CD came along. Teenagers (as I was then) can tell where 20kHz brickwall filters harm music, but at last, at long last, the music was almost completely pure. It did not waver or wobble. It was not interrupted by ticks and pops, nor by fuzz. Its quality was identical from beginning to end. There was no mourning that the beautiful passages of “En Saga” were harmed by being close to the end of the LP side. There was silence between the tracks or in the rests. Just like in the concert hall or recording session. And, later, it became clear that the recorded sound did not need to be sanitized (albeit, in the hands of a mastering engineer, very sympathetically and musically indeed) to survive the transition from tape to vinyl groove. After this, all else was candlelight. We didn’t have gas in the village where I grew up. (Note to the youngest readers: find Karajan’s statement on digital audio.)

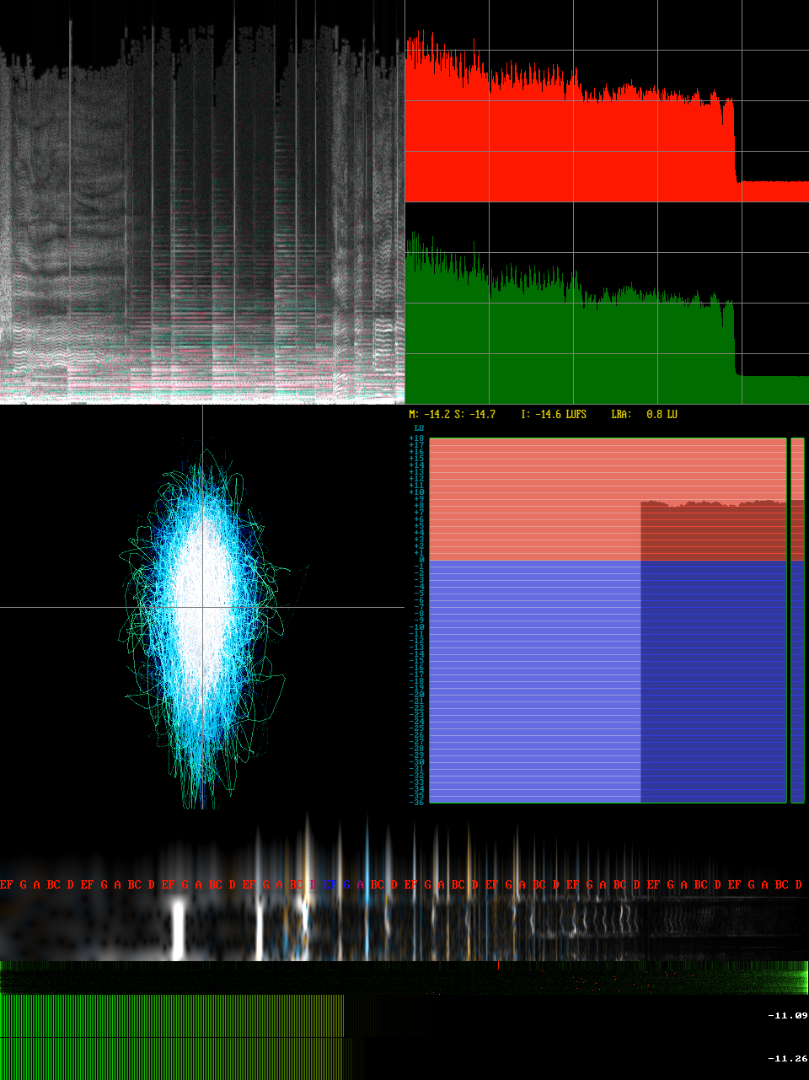

Apart from the gradual increase in amplifier efficiency and very occasional leaps forward in speaker technology (my main speakers are twenty years old, though a better sub was added recently), to answer the original question, I have heard nothing since the advent of interruption-free recordings, whether digital or analogue, that improves my enjoyment of music or drama, except for one thing. The ability to compress the music to suit my listening environment is my primary nod to convenience. Where necessary, my in-car or ‘party’ music on memory sticks has broadcast-style processing added so I never touch the volume control anywhere on the road or while people are chatting over the guacamole (home made) and Cava.

What’s left? Convenience; curation; accessibility, discovery; that’s all, really — and a means of paying musicians properly, of course.

As I become older, one thing intrigues me. If I become thoroughly deaf, and need a cochlear implant, could I tune my computer, as a musical instrument, to the frequency channels and be able to hear (or compose) music arranged especially for those channels? Could that be a thing? Can there be music composed or arranged specifically to be heard at its best through the limited-pitch channels of a cochlear implant, so that permanently and profoundly deaf people might choose to try experiencing music in this way too?

I’d like to thank Mike Brown, very senior audio engineer and radio presenter, for asking the question that provoked this ramble. His website is http://www.originalsound.co.uk/, and you can read about his many regular radio shows here: https://www.facebook.com/mikeonthewireless/

Illustrations are not mine; but are similar items seen on eBay or other websites

, the autochanger based on the SP25, into a polished brown radiogram cabinet and wired the crystal cartridge to the input of the built-in valve radio/amplifier. The cabinet had a richly toned single speaker underneath, and this system of glowing radio dial and filaments played his classical LPs, the 7-inch singles my mother inherited from her DJ brother, and my children’s records, together with some shellac 78s from second-hand shops and relatives, played by

, the autochanger based on the SP25, into a polished brown radiogram cabinet and wired the crystal cartridge to the input of the built-in valve radio/amplifier. The cabinet had a richly toned single speaker underneath, and this system of glowing radio dial and filaments played his classical LPs, the 7-inch singles my mother inherited from her DJ brother, and my children’s records, together with some shellac 78s from second-hand shops and relatives, played by  and speech recordings too from companies like

and speech recordings too from companies like  replaced in 1969 by a black box into which my father had installed a Sinclair IC10-based 10W amp, which lasted through the replacement of the cartridge with a ceramic item in 1971, then he built (with me holding the circuit-boards steady sometimes) the Practical Electronics Gemini stereo amp set in 1972. In the years of mass-market stereo LPs on “

replaced in 1969 by a black box into which my father had installed a Sinclair IC10-based 10W amp, which lasted through the replacement of the cartridge with a ceramic item in 1971, then he built (with me holding the circuit-boards steady sometimes) the Practical Electronics Gemini stereo amp set in 1972. In the years of mass-market stereo LPs on “ “But it was a stereo hi-fi to US” (to misquote Eric Idle), and the leap forward into “sound sculpted in space” was never regretted.

“But it was a stereo hi-fi to US” (to misquote Eric Idle), and the leap forward into “sound sculpted in space” was never regretted. them on the Radio 3 concerts. Sometimes the pitch wavered slowly. Nearly always the sound had a ‘fuzz’ with it toward the end of a side, particularly on French horns, muted brass and sopranos. None of this happened when I taped a cassette off the radio, and it was a crying shame that all recorded music for the masses had this gauze of dirt, this veil in front of it. I learned where every scratch was in the quiet passages of the symphonies and chamber music on the shelf, and was almost surprised when those noises didn’t occur where expected on radio performances. My parents didn’t mind the interruptions, but I knew this rubbish was not music, even though the frequency response ran smoothly from bottom to top and the amplifier’s distortion was almost below measurement. And it was sad that one poorly set-up pickup or arm could damage a precious recording for ever.

them on the Radio 3 concerts. Sometimes the pitch wavered slowly. Nearly always the sound had a ‘fuzz’ with it toward the end of a side, particularly on French horns, muted brass and sopranos. None of this happened when I taped a cassette off the radio, and it was a crying shame that all recorded music for the masses had this gauze of dirt, this veil in front of it. I learned where every scratch was in the quiet passages of the symphonies and chamber music on the shelf, and was almost surprised when those noises didn’t occur where expected on radio performances. My parents didn’t mind the interruptions, but I knew this rubbish was not music, even though the frequency response ran smoothly from bottom to top and the amplifier’s distortion was almost below measurement. And it was sad that one poorly set-up pickup or arm could damage a precious recording for ever. “Musicassettes” too often sounded muddy, though we rescued a reel-to-reel deck to play home-recorded tapes well; but no decent tapes were available unless recorded from Radio 3 concerts or the

“Musicassettes” too often sounded muddy, though we rescued a reel-to-reel deck to play home-recorded tapes well; but no decent tapes were available unless recorded from Radio 3 concerts or the  the CD came along. Teenagers (as I was then) can tell where 20kHz brickwall filters harm music, but at last, at long last, the music was almost completely pure. It did not waver or wobble. It was not interrupted by ticks and pops, nor by fuzz. Its quality was identical from beginning to end. There was no mourning that the beautiful passages of “

the CD came along. Teenagers (as I was then) can tell where 20kHz brickwall filters harm music, but at last, at long last, the music was almost completely pure. It did not waver or wobble. It was not interrupted by ticks and pops, nor by fuzz. Its quality was identical from beginning to end. There was no mourning that the beautiful passages of “